Here is my blog-style documentation of my reverse enginnering progress. The book I am referring to is from Bruce Dang titled “Practical Reverse Engineering”. I will share my progress and insights as I explore the concepts and techniques in the books.

Overview

The x86 architecture is based off Intel 8086 processor which focus on 32-bit implementation, also known as (IA-32).

Operating Modes:

- Real Mode Operation:

- Provided essentially for backward-compatibility with 8086 and 80816 programs

- Initial processor state upon power-on

- Only the base instruction set of the processor can be used

- Protected Mode Operation:

- Able to address up to 4GB of memory

- Supports direct mapping to physical RAM or virtual-to-physical translation via mapping

The extension of 32-bit architecture is called x64 or x86-64. However this chapter discuss the x86 architecture operating in protected mode.

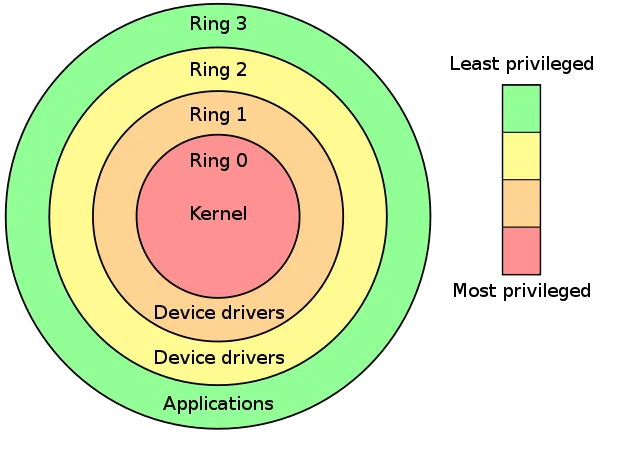

x86 architecture supports the concept of privilege separation by ring levels:

- Ring 0:

- Highest privilege level

- Able to modify all system kernel settings

- Full access to hardware, like I/O devices and managing memory

- Ring 1:

- Intermediate privilege level

- Rarely used directly because many OS use ring 0 for device drivers

- Ring 2:

- Similar to Ring 1

- Not widely used

- Ring 3:

- User mode applications

- Rely on system calls to request services from the kernel

- User space - isolates user applications from the core of OS

The ring level is encoded in the cs register, referred as current privilege level (CPL)

Register Set and Data Types

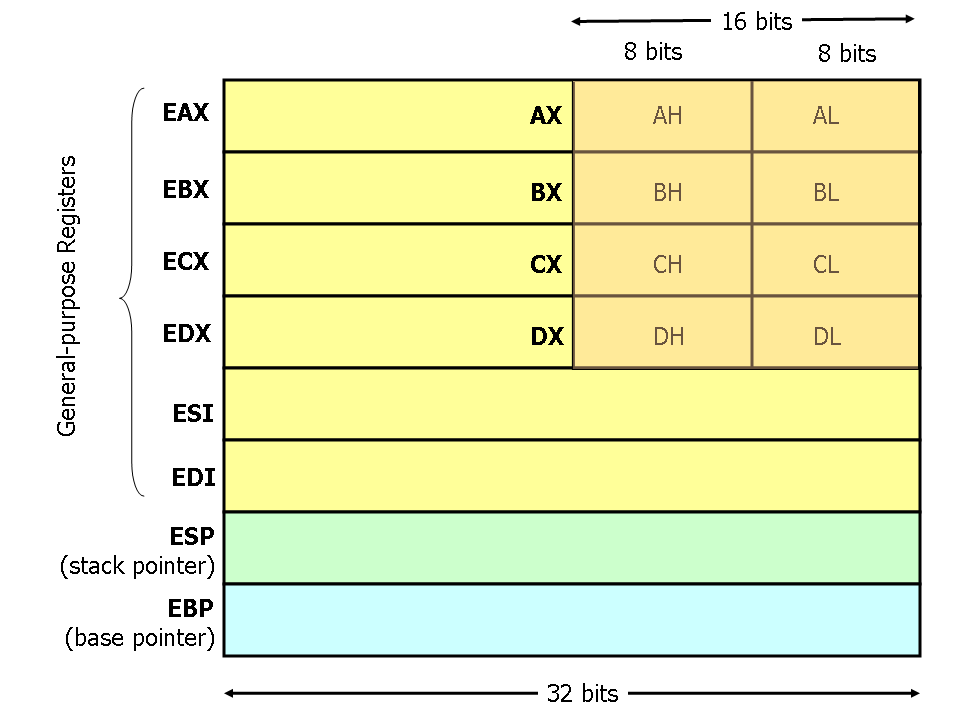

In x86 architecture, there are 8 32-bit general purpose registers.

From the image, we can notice EAX, EBX, ECX and EDX can be divided into 8- and 16 bits registers.

From the image, we can notice EAX, EBX, ECX and EDX can be divided into 8- and 16 bits registers.

| Register | Purpose |

|---|---|

| EAX | Used for arithmetic operations and as a general-purpose data register |

| EBX | Used as a pointer to data in memory, often in indexing operations |

| ECX | Used as a loop counter in iterations and for shifts/rotations in bit-level operations |

| EDX | Used for I/O operations, multiplication/division, and holding extra data during computations |

| ESI | Source in string/memory operations, pointing to data being read |

| EDI | Destination in string/memory operations, pointing to where data is written |

| ESP | Stack pointer, pointing to the top of the stack |

| EBP | Base frame pointer, pointing to the base of the current stack frame |

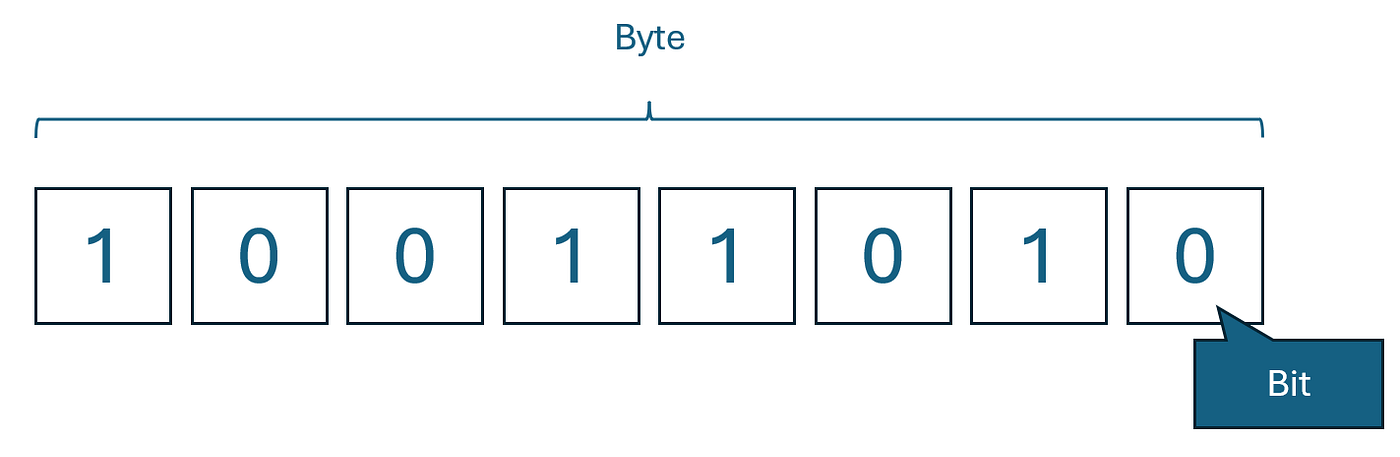

Common data types:

- Byte: 8 bits, stores single byte of data (0 to 255)

- Word: 16 bits, stores 16-bit value (0 to 65,535)

- Double Word: 32 bits, stores 32-bit (0 to 4,294,967,295)

- Quad Word: 64 bits, stores 64-bit value (0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615)

Moreover, there are registers which is used for managing low-level system mechanisms and execution states. Those registers are:

| Register | Purposes |

|---|---|

| EFLAGS | Stores status of arithmetic operations and execution states. It is used for conditional branching |

| CR0 | Control system-level mechanism like enabling/disabling paging |

| CR2 | Contains linear address that caused a page fault |

| CR3 | Holds the base address of the paging data structure |

| CR4 | Controls hardware virtualization settings |

| DR0-DR7 | Used to set memory breakpoints for debugging |

Instruction Set

For the sake of my slow learning progress, I am going to learn x86 instruction set first, not going to cover ARM, later on will do that. Also sticking to Intel syntax.

Now lets dive into x86 instruction set, it give direction for data movement between registers and memory. The movement can be classified into five general methods:

- Immediate to register

- Register to register

- Immediate to memory

- Register to memory and vice versa

- Memory to memory

If we refer to Intel’s 64 and IA-32 documentation, Chapter 5 (Instruction Set Summary) under 5.1 General-Purpose Instructions. Instructions can be divided into:

| Instructions | Functions |

|---|---|

| Data transfer instructions | Move data between memory and the general-purpose and segment registers. Perform specific operations: conditional moves, stack access and data conversion |

| Binary Arithmetic Instructions | Performs basic binary integer computations on byte, word and doubleword integers located in memory and/or the general purpose integers. |

| Decimal Arithmetic Instructions | Performs decimal arithmetic on binary coded decimal (BCD) data |

| Logical Instructions | Performs basic AND, XOR, and NOT logical operations on byte, word and doubleword values. |

| Shift and Rotate Instructions | Shift and rotate the bits in words and doubleword operands |

| Bit and Byte Instructions | Test and modify individual bits in words and doubleword operands. Byte instructions set the value of a byte operand to indicate the status of flags in the EFLAGS registers |

| Control Transfer Instructions | Provide jump, conditional jump, loop and call and return operations to control program flow |

And many other more, I will try to cover the rest with some examples in some other time.

Data Movement

MOV move a register or immediate to register

mov esi, 0F003Fh ; set ESI = 0xF003

mov esi, ecx ; set ESI = ECX

move data to/from memory, it use square brackets [] to indicate memory access.

NOTE: LEA instruction which also use [] but does not actually reference memory

mov dword ptr [eax], 1 ; set memory address EAX at 1

mov ecx, [eax] ; set ECX to the value at address EAX

mov [eax], ebx ; set the memory at address EAX to EBX

mov [esi+34h], eax ; set memory address at (ESI+34h) to EAX

mov eax, [esi+34h] ; set EAX to the value at address (EAX+34)

mov edx, [ecx+eax] ; set EDX to the value at address (ECX + EAX)

Based on the assembly code above, we can translate that into pseudo C programming language with the concept of pointers.

*eax = 1;

ecx = *eax;

*eax = ebx;

*(esi+34) = eax;

eax = *(esi+34);

edx = *(ecx+eax);

MOVSB/MOVSW/MOVSD This instruction move data with 1-,2-, or 4-byte granularity between two memory address. It implicitly use EDI/ESI as the destination/source address respectively. This instruction used to implement string or memory copy functions when the length is known at compile time. Moreover, it automatically update the source/destination address depending on the direction flag (DF) flag in EFLAGS. To put it simply:

ESI:Points to the source buffer (srcin C)EDI:Points to the destination buffer (destin C)ECX:Holds the length of the memory to copy (number of iteration)EFLAFS (DF): Determine whether the copy move forward (DF=01) or backward (DF=1)

Consider this example of memcpy in C:

int main() {

char src[10] = "ABCDEF";

char dest[10];

memcpy(dest,src,8); //copy 8 bytes from src to dest

return 0;

Now here is the translation to assembly:

mov esi, src ; load source address to ESI register

mov edi, dest ; laod destination address into EDI

mov ecx, 8 ; set the count of bytes to copy

rep movsb ; repeat MOVSB (byte-by-byte copy) for ECX times

To note, the REP is used to automated the loop in order to reduce the overhead process of manually iterating over memory locations. (PS: I didnt cover SCAS,STOS and LODS instructions, will do it as a separate section)

Arithmetic Operations

The assembly instructions set has basic arithmetic operation (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) and bit-level operations (AND, OR, XOR, NOT, shifts). Most are straightforward, except multiplication and division, which may require additional handling. Here is the example:

add esp, 14h ; esp = esp + 0x14h

sub ecx, eax ; ecx = ecx - eax

sub esp, 0Ch ; esp = esp - 0xc

inc ecx ; ecx = ecx + 1

dec edi ; edi = edi - 1

or eax, 0FFFFFFFFhh ; eax = eax | 0FFFFFFFFhh

and ecx, 7 ; ecx = ecx & 7

xor eax, eax ; eax = eax ^ eax

not edi ; edi = ~edi

shl cl,4 ; cl = cl << 4

shr ecx,1 ; ecx = ecx >> 1

rol al, 3 ; rotate AL left 3 positions

ror al, 1 ; rotate AL right 1 position

- Youtube video link on Bit Operations: Bitwise Operations & Bit Masking

- Youtube video link on Binary Shifts: Binary Shifts Tutorial

Another interesting to point out, is that SHL and SHR are typically used to optimize multiplication and division operations where the multiplicand and divisor are a power of two. The reason is that the shift operations substitutes a less costly computing process for a more costly one, this kind of optimization is frequently referred to as strength reduction.

MUL and IMUL instructions is for both unsigned and signed multiplication instructions respectively. However, there are different form of usage with MUL and IMUL. The key differences are:

MULonly operates on register or memory valuesIMULhas three forms- Single Operand Form (same like

MUL) - Two Operand Form (

IMUL reg1, reg2/mem->reg1 = reg1 *reg2/mem) - Three Operand Form (

IMUL reg1, reg2/mem, imm->reg1 = reg2 * imm)

- Single Operand Form (same like

DIV and IDIVinstructions is for both unsigned and signed division instruction respectively. However, for DIV and IDIV take only one parameter which is the divisor. The key point is that the instruction depends on the divisor’s size.

DIVandIDIVtake in this form:DIV/IDIV reg/mem- 8-bit divisor: Dividend in

AX. Quotient is stored inAL, remainder inAH - 16-bit divisor: Dividend in

DX:AX. Quotient is stored inAX, remainder inDX - 32-bit divisor: Dividend is in

EDX:EAX. Quotient is stored inEAX, remainder inEDX

Stack Operations and Function Invocation

The Stack

Stack is a region of memory which is use to manage function calls, local variables and control flow operations. It operates with the principle of Last In, First Out (LIFO), where most recently pushed item is the first to be popped.

- Push : to put something on top of the stack

- Pop: to remove an item from the top ![[Pasted image 20241216182705.png]] The stack movement is controlled by ESP and the value of increment or decrement value is 4, ensuring double-word alignment. To note, the ESP register always point to the top of the stack, and its value changes with stack operations. For example:

- PUSH: ESP decrease (stack grows downward) to allocate space for the pushed value

- POP: ESP increase (stack shrinks upward) to remove the top value

Here is a simple function call example in assembly

; Main program

PUSH EBP ; save the previous base pointer

MOV EBP, ESP ; set up the new base pointer

PUSH 10 ; push a parameter to the stack (ex: 10)

CALL myFunction ; call the function

; After the call

MOV ESP, EBP ; Clean up the stack

POP EBP ; Restore the previous base pointer

RET ; Return to the caller

; Function Definition

myFunction:

PUSH EBP ; Save the previous base pointer

MOV EBP, ESP ; Set up the new base pointer

SUB ESP, 4 ; Allocate space for local variable(s)

; Do something with local variables and parameters

MOV [EBP-4], 5 ; Store value in local variable

POP EBP ; Restore the base pointer

RET ; Return to the caller

Calling Conventions

A calling convention defines the rules for how function calls operate at the machine level. These conventions are part of the Application Binary Interface (ABI) of a system and specify details like:

- How parameters are passed (via the stack, registers or both)

- The order in which parameter are passed (left-to-right or right-to-left)

- Where the return value is stored (stack or register)

Popular calling conventions:

- CDECL: common in C and C++ compilers. Parameters are passed on the stack (right-to-left order), and the caller cleans up the stack

- STDCALL: used in Windows API functions. Similar to CDECL but the callee cleans up the stack

- THISCALL: used for calling C++ member functions. Then this pointer is passed in the ECX register, and other parameters are passed on the stack

- FASTCALL: optimized calling convention where the first few parameters are passed in registers (ECX, EDX) and the rest are passed on the stack.

CALL and RET instructions:

- CALL:

- Pushes the return address on the stack

- Changes the EIP to target address of the call, effectively transferring control to the target function

- RET:

- Pops the return address from the stack into EIP, resuming execution to the return address, which was the address stored by the preceding CALL

Control Flow

As we are familiar with control flow statements in higher level languages which utilizes keywords such as if/else, while/for loops, switch/case statements, in lower level assembly it implements differently by using CMP, TEST, JMP, Jcc (conditional jumps) and EFLAGS registers.

| EFLAGS | Operations |

|---|---|

| ZF/Zero Flag | Set if the result of the previous arithmetic operation is zero |

| SF/Sign Flag | Set to the most significant bit of the result |

| CF/Carry Flag | Set when the result requires a carry. It applies to unsigned numbers |

| OF/Overflow Flag | Set if the result overflows the max size. It applies to signed numbers |

With both EFLAGS and the operands, it can produce up to 16 conditional codes, here is the summarized of the common ones:

| Conditional Code | Description | Machine Description |

|---|---|---|

| B/NAE | Below/Neither Above nor Equal Used for unsigned operations |

CF=1 |

| NB/AE | Not Below/Above or Equal Used for signed operations |

CF=0 |

| E/Z | Equal/zero | ZF=1 |

| NE/NZ | Not Equal/not zero | ZF=0 |

| L | Less than/Neither Greater not Equal Used for signed operations |

(SF ^ OF) = 1 |

| GE/NL | Greater or Equal/Not Less Than. Used for signed operations |

(SF ^ OF) = 0 |

| G/NLE | Greater/Not Less nor Equal. Used for signed operations |

((SF ^ OF) | ZF) = 0 |

- CMP: Compares two operands by subtracting them but only updates EFLAGS (not the actual result), used for setting condition codes

- TEST: Perform a logical AND between operands but only updates EFLAGS (not the actual result), used for setting condition codes

If-else

Lets take a look at C code first and then we relate it to assembly. Here is the simplified C if-else:

if (value == 0) {

return;

}

// other code

Here it checks whether value is 0, so in assembly it translates to this:

test eax, eax ; check condition

jz location ; jump if zero (condition met)

; Code block if condition false

location:

; Code block if condition true

In assembly, whether a high level of if/else to test or cmp instruction depends on type of comparison being performed:

CMPinstruction- Used for explicit comparison

- Comparing two values like

if (a > b)orif (x == y)

TESTinstruction- Used for bitwise checks

- Performs a bitwise

ANDbetween the two operands without modifying them - Checking bit masks or non-zero values

if (x & 0xFF)

Switch/Case

Same thing, we going to look an example of C and then translates back to assembly.

void example(int value) {

switch (value) {

case 1:

printf("Case 1\n");

break;

case 2:

printf("Case 2\n");

break;

default:

printf("Default case\n");

break;

}

}

Here is how it translates to assembly:

example:

cmp eax, 1

je case_1

cmp eax, 2

je case_2

jmp default_case

case_1:

; printf("Case 1\n")

jmp end

case_2:

; printf("Case 2\n")

jmp end

default_case:

; printf("Default case\n")

end:

ret

For switch-case statements, it uses a combination of CMP and conditional JMP instructions. However, compiler will commonly build a jump table to reduce the number of comparisons and conditional jumps. For the default case, it is used to handle using an unconditional JMP to the default case code if there is no matches found.

While Loop

While loop in C:

while (condition) {

// loop body

}

Translates to assembly:

loop_start:

test ecx, ecx ; check condition

jz loop_end ; exif if condition false

; loop body

jmp loop_start ; repeat

loop_end:

For while loop, it will test the conditions first and then jumps if false. Notice there is a JMP loop_start, it means a backward jump which create a loop and it uses TEST for conditional checking

For Loop

For loop in C:

for (int i=0; i < count; i++) {

//loop body

}

Translates to assembly:

mov ecx, count ; Load count into ecx

xor eax, eax ; Initialize i (eax) to 0

loop_start:

cmp eax, ecx ; Compare i (eax) with count (ecx)

jge loop_end ; Exit loop if i >= count

; Loop body code here

inc eax ; Increment i

jmp loop_start ; Jump back to start of loop

loop_end:

; Continue after the loop

The loop starts by initializing i to 0 using xor eax, eax. Next, it compares i with count using cmp eax, ecx and exits the loop if i greater than or equal to count using jge. Inside the loop, the body executes, and i is incremented by 1 with inc eax. At the end, the jmp instruction loops back to the start of the next iteration.

System Mechanism

To get a better appreciation of the architecture, this section discusses two fundamental system-level mechanisms:

- Virtual address translation

- Exception/Interrupt handling

Address Translation

Virtual addresses are those used by instructions executed in processor when paging is enabled. On x86 systems with physical address extension (PAE) support, a virtual memory address can be divided into three indices into three tables and offset:

- Page directory pointer table (PDPT)

- Page directory (PD)

- Page table entry (PTE)

The process of address translation:

- Virtual page number translated to the physical page number

- Page offset untranslated

- Page Table keeps mappings for every virtual page -> physical page

The address translation process revolves around these three tables and the CR3 registers. The function of CR3 register in virtual addressing is that it holds the physical base address of the PDPT.

Interrupts and Exceptions

Interrupts:

- Generated by hardware devices

- Asynchronous events that demand processor attention

- Associated with an interrupt number used to index into an interrupt vector table, which works like an array of function pointers

- Processor executes the function pointed to by the table and resumes previous execution

Exceptions:

- Generated during instruction execution due to errors or special instructions

- Two types:

- Faults:

- Correctable exceptions

- Execution resumes at the same instruction after corrections

- Useful for detecting anti-debugging mechanisms that leverage faults

- Traps:

- Triggered by special instructions (

SYSENTERorINT 0x80for system calls) - Able to identify and reveal the system-level operations of malware

- Triggered by special instructions (

- Faults:

OS commonly implements system calls through interrupts and exception mechanism.

References:

- x86 Assembly/Protected Mode

- What are the rings of the x86 architecture?

- x86 registers, memory addressing, instructions and calling convention

- Intel 64 and IA-32 Architecture Software Developer Manuals

- Github Gist on memcpy

- Stack Operations and Function Calls in x86

- Reverse Engineering for Noobs Part 1