Table of Contents

Yet another technical blog, but here is an interesting topic to cover by sharing a theoretical computer science knowledge along with a tool called Angr. I came across this tool from BrunnerCTF and used it in UofTCTF.

Angr is an open source binary analysis that runs with Python, it combines both static and dynamic analysis to perform task such as:

- Control-flow graph recovery

- Symbolic execution

- Automatic ROP chain building

- Automatic binary hardening

- Automatic exploit generation

For this blog, I going to cover about symbolic execution and methodology to use angr solving reverse engineering challenge that suits this technique. Before hand, let’s cover the key concept of symbol executions.

What is Symbolic Execution

The core idea of symbolic execution is about executing a program abstractly, not with a concrete inputs. It uses symbolic variables such as α, β, γ instead of actual values. With that, one symbolic execution able to represent many concrete execute that follows the same path.

Let’s use a simple C program and Assembly to understand better.

int check(int input) {

if(input != 10) return 0;

if(input +5 != 20) return 0;

return 1;

}

From the logic of the code, here is what we can derive into mathematically:

x = 10-> first check passedx+5 = 15-> second check failed (15 != 20)

We picked 10 to try to satisfy the first check, we might try more numbers but it will be exhaustive. Here is where symbolic execution is powerful, instead of picking 10, we keep x = α and explore all paths simultaneously and collecting path constraints:

- Path 1:

α ≠ 10→ return 0 - Path 2:

α = 10ANDα + 5 = 20→ return 1 (but this is unsatisfiable — no such α exists) - Path 3:

α = 10ANDα + 5 ≠ 20→ return 0

A symbolic executor would hand those constraints to a SAT/SMT solver and discover that the return 1 path is unreachable.

Here is how it will appear at lower level, given our C code is compiled to 64 bit architecture.

check:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov [rbp-4], edi ; store input on stack

cmp [rbp-4], 10 ; compare input with 10

jne .return_0 ; if input != 10, jump to return 0

mov eax, [rbp-4] ; load input

add eax, 5 ; eax = input + 5

cmp eax, 20 ; compare with 20

jne .return_0 ; if input+5 != 20, jump to return 0

mov eax, 1 ; return 1

jmp .done

.return_0:

mov eax, 0 ; return 0

.done:

pop rbp

ret

Now we map the symbolic execution directly onto the assembly. Instead of a concrete value, the register holds an arbitrary value like a

[rbp-4] = α ; symbolic input stored on stack

cmp [rbp-4], 10 ; evaluates α - 10

jne .return_0 ; branch condition: is α ≠ 10 ?

At this jne instruction, the symbolic executor forks into two paths:

- Branch taken:

a ≠ 10: jumps to.return_0 - Branch not taken:

a = 10: continues next instruction,eax = a + 5

After adding 5 to the arbitrary value of a, we will reach at the second compare instruction

cmp eax, 20 ; evaluates (α+5) - 20

jne .return_0 ; branch condition: is α+5 ≠ 20 ?

At the second jne instruction, there is another fork:

- Branch taken:

α + 5 ≠ 20: jumps to.return_0 - Branch not taken:

α + 5 = 20

With this process, SMT solver will come up with constraints of α = 10 AND α+5 = 20. We able to notice when the fork happens and the path constraints are just the accumulated branch conditions leading to that point. Each branch instruction is a decision point, and symbolic execution explores both sides simultaneously rather than committing to one.

Challenge 1: UofTCTF’s Symbol of Hope challenge

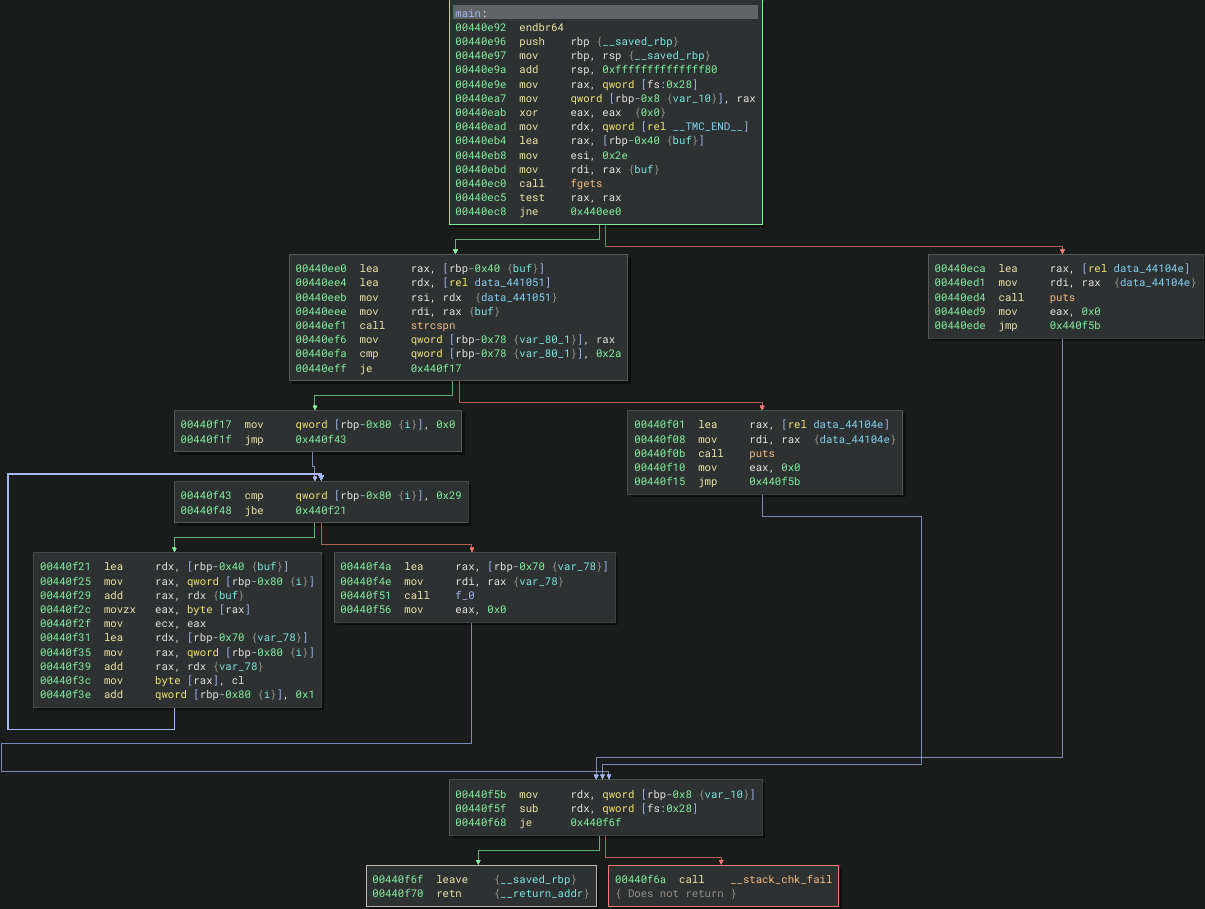

This is a reverse engineering challenge named Symbol of Hope, which is clear hinting about a symbol execution challenge. The challenge binary is UPX packed, after unpacking and dump into a decompiler, here is what we will notice in the main function:

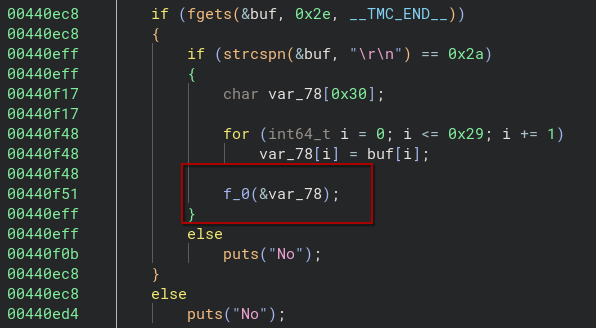

In the main function, the binary uses fgets to take input and strcspn to check 42 length of characters then proceed to a for loop and passed into a transformation chain check for the flag.

From function f_0, if the check passed, it proceed to f_1, then to f_2, then to f_3, then to f_4 … you get the idea 😅

Each f_N function applies a single byte transformation to a specific index of the input buffer, and then tail-calls f_N+1. This is a linear chain of transformation where there is no branching, no dispatch table. It is just a long sequence of operations like:

arg1[0xa] *= -0x31; // f_0

arg1[0x19] = ror8(...) // f_1

arg1[7] = ~arg1[7]; // f_2

arg1[0x22] -= 0x79; // f_3

...

memcmp(arg1, &expected, 0x2a) // f_4200

Here is why symbolic execution is absolute overkill for this challenge. This is purely reversible transformation chain with no branches. Every operation (*=, -=, ~, rol8, ror8) is invertible:

x *= k→x *= modular_inverse(k, 256)x -= k→x += kx = ~x→x = ~x(self-inverse)x = ror8(x, n)→x = rol8(x, n)x = rol8(x, n)→x = ror8(x, n)

Now here is the core idea with solving this challenge with angr, instead running the binary with a debugger and supply with a real input and hoping it prints “Yes”, we let angr to explore the binary symbolically, by using a placeholder input that represents all possible 42 characters string at once. Here is how:

Step 1: Load the binary

import angr

import claripy

# remember to UPX unpack the binary

proj = angr.Project("./checker", auto_load_libs=False)

angr.Project is the letting it to know which binary that we want to supply and the auto_load_libs=False is telling angr not to bother about loading system libraries such as libc. Angr has it built-in summaries for standard functions like the one we notice in the decompiled code such as fgets and memcmp. This way it will keeps things fast and avoid angr getting lost inside library internals.

Step 2: Create a symbolic input

flag = claripy.BVS("flag",42 * 8)

This is the heart of symbolic execution where instead giving a concrete string like "uoftctf{flag_string}", we create a symbolic bitvector which is 42 bytes (42 x 8 bits). Its value is completely unknown at this point. It represent every possible 42 ASCII character string value simulateneously. claripy is the constraint solving library angr uses under the hood. BVS stands for BitVector symbolic.

Step 3: Create the initial state

state = proj.factory.call_state(

0x440e92,

stdin=angr.SimFile(name='stdin',content=flag,size=42)

)

A state in angr is a snapshot of everything which includes registers, memory, stacks and constraints that the solver will be accumulating. Here we create a starting state at the address of main function which is at 0x440e92.

The stdin=angr.SimFile() function wires our symbolic flag variable into the program’s standard input. So when the binary calls fgets to read from stdin, it will receive our symbolic variable instead of real bytes. Angr will track how every byte gets used throughout execution.

Step 4: Adding constraints to guide the solver

for b in flag.chop(8):

state.solver.add(b != 0x0a) # no newline

state.solver.add(b != 0x0d) # no carriage return

state.solver.add(b >= 0x20) # printable ASCII

state.solver.add(b <= 0x7e)

flag.chop(8) splits our 42-byte bitvector into 42 individual 1-byte pieces. For each byte we add constraints, which is the rules that any valid solution must satisfy. We state a rule where every byte must be a printable ASCII character and not a newline.

Adding these upfront is helpful as angr will narrow the search space enormously before exploration even begins. Besides with the 42-byte constraint, we able to narrow down even more as we know the specific flag format for this challenge which is uoftctf{ and the last byte is }. Now instead of solving for 42 completely unknown bytes, the angr solver need to solve for the remaining 33 bytes in the middle. Here is how we can specify in the script:

prefix = b"uoftctf{"

for i, c in enumerate(prefix):

state.solver.add(flag.get_byte(i) == c)

state.solver.add(flag.get_byte(41) == ord('}'))

Step 5: Hook memcmp

class ForceMemcmp(angr.SimProcedure):

def run(self, s1, s2, n):

data1 = self.state.memory.load(s1,0x2a)

data2 = self.state.memory.load(s2,0x2a)

self.state.solver.add(data1 == data2)

return claripy.BVV(0, 32)

proj.hook_symbol('memcmp',ForceMemcmp())

This part is for the last function f_4200 because it calls memcmp(arg1,&expected, 0x2a) to check our input. Normally angr would symbolically execute through memcmp actual implementation which is resource expensive. Instead we replace it entirely with SimProcedure with angr custom function summary. Our fake memcmp does only two things:

- Adds a constraints saying arg1 buffer must be equal to expected buffer

- Returns 0 if the binary takes the “Yes” path

Step 6: Explore

simgr = proj.factory.simulation_manager(state)

simgr.explore(

find=lambda s: b"Yes" in s.posix.dumps(1),

avoid=lambda s:b"No" in s.posix.dumps(1)

)

The simulation manager is what actually runs the symbolic execution. Think of its as managing a collection of states. At every branch in the binary, it can fork into multiples states to represent each possible path.

explore drives it forward:

find- keep going until a state reaches a point where stdout contains “Yes”avoid- if a state’s stdout contains “No”, immediately discard it and stop exploring that path

This way it prunes the search tree aggressively. The moment a path is headed toward a “No” output, angr drops it entirely.

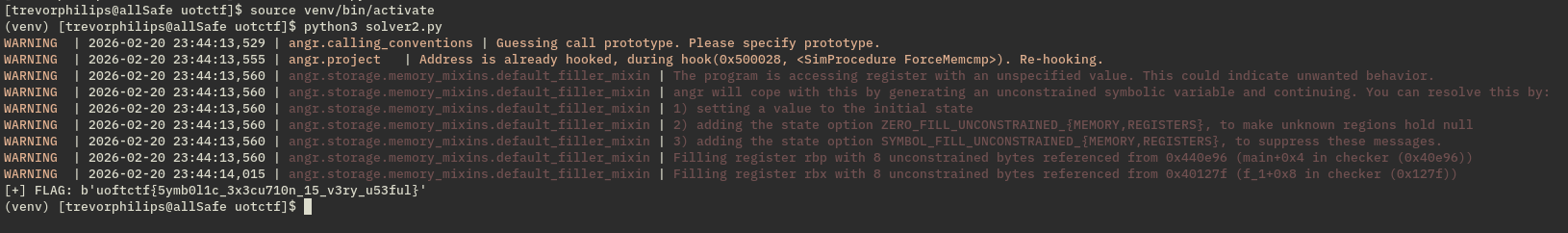

Step 7: Extract flag if correct path explored by angr

solution = simgr.found[0].solver.eval(flag, cast_to=bytes)

print("[+] FLAG:",solution)

Here is the full solution script:

import angr

import claripy

BIN = "./checker"

proj = angr.Project(BIN, auto_load_libs=False)

flag = claripy.BVS("flag", 42 * 8)

# Constraints

state = proj.factory.call_state(0x440e92, stdin=angr.SimFile(name='stdin', content=flag, size=42))

for b in flag.chop(8):

state.solver.add(b != 0x0a)

state.solver.add(b != 0x0d)

state.solver.add(b >= 0x20)

state.solver.add(b <= 0x7e)

prefix = b"uoftctf{"

for i, c in enumerate(prefix):

state.solver.add(flag.get_byte(i) == c)

state.solver.add(flag.get_byte(41) == ord('}'))

# Hook memcmp to force equality and extract constraint

class ForceMemcmp(angr.SimProcedure):

def run(self, s1, s2, n):

data1 = self.state.memory.load(s1, 0x2a)

data2 = self.state.memory.load(s2, 0x2a)

self.state.solver.add(data1 == data2)

return claripy.BVV(0, 32)

proj.hook_symbol('memcmp', ForceMemcmp())

simgr = proj.factory.simulation_manager(state)

simgr.explore(

find=lambda s: b"Yes" in s.posix.dumps(1),

avoid=lambda s: b"No" in s.posix.dumps(1)

)

assert simgr.found, "No solution found"

solution = simgr.found[0].solver.eval(flag, cast_to=bytes)

print("[+] FLAG:", solution)

The key idea here is that we never need to know what the transformation do mathematically. We just let angr to bullds up a giant system of equations automatically by watching how the symbolic bytes flow through all 4200 functions and spit out the flag.

Next part, we will continue with BrunnerCTF challenge which is slightly complex. Below I have attach some resources for your references regarding about symbolic execution and angr.