Table of Contents

- Appetizer

- Basic x86/x64 Assembly Instructions

- Structure of an Assembly Program

- Syscall Calling Conventions

- Stack Management

Appetizer

The art of writing shellcode sits at the intersection of low-level programming and security research, demanding both technical precision and creative problem-solving. While many security professionals can utilize existing shellcode, developing it from scratch requires a deep understanding of assembly language and various intricate techniques that make shellcode both functional and reliable

Shellcode development present unique challenges that set it apart from traditional assembly programming. The code must be entirely self-contained and carefully crafted to avoid null bytes (0x00), which would prematurely terminate the shellcode when used with string functions like strcpy(). This constraint alone requires specific techniques and tricks that regular assembly programming does not demand.

Approaches for Shellcode Development:

- Stack-based data manipulation

- Call-based addressing techique

The stack-based approaches pushes data onto the stack during execution, while the call-based method cleverly uses the call instruction to store data address on the stack. Before diving into developing shellcode, lets explore assembly.

Basic x86/x64 Assembly Instructions

Before getting in assembly coding, lets refresh on processor registers and its functions in x86. Registers is used as a high-speed storage locations which is efficient in executing instructions. As mentioned earlier, some registers server specific functions while others are general-purpose and can be freely used in assembly programming

Categories of Registers

- General Purpose Registers (GPR)

- EAX (Accumulator): Used for arithmetic operations and function return values

- EBX (Base): Used as a pointer to data in memory

- ECX (Counter): Used for loop iteration and shifting operations

- EDX (Data): Used for I/O operations and storing function return values

- ESI/EDI (Source and Destination): Used for memory operations with

movsandlods

- Pointer and Stack Register

- ESP (Stack Pointer): Points to the top of the stack and adjusts as functions push and pop values

- EBP (Base Pointer): Used to reference function arguments and local variables

- Instruction Pointer:

- EIP (Instruction Pointer): Stores the memory address of the next instruction to be executed

The registers mentioned above is used in 32-bit architecture, for 64-bit architecture (x86-64), these registers expand its size to RAX, RBX, RCX, RDX and additional R8 to R15 to provide extra data and arguments.

Now, we move to understanding (minimum) assembly instruction for shellcoding.

| Instruction | Name/Syntax | Description |

|---|---|---|

| mov | Move instructionmov <dest>, <src> |

Used to set initial values Move the value from <src> into <dest> |

| add | Add instructionadd <dest>, <src> |

Used to add values Add the value in <src> to <dest> |

| sub | Subtract instructionsub <dest>, <src> |

Used to subtract values to the stack Subtract the value in <src> to <dest> |

| push | Push instructionpush <target> |

Used to push values to the stack |

| pop | Pop instructionpop <target> |

Used to pop values from the stack |

| jmp | Jump instructionjmp <address> |

Used to change to EIP to a certain address |

| call | Call instructioncall <address> |

Used like a function call, to change the EIP to a certain address, while pushing a return address to the stack Push the address of the next instruction to the stack, and the change the EIP to the address in <address> |

| lea | Load effective addresslea <dest>, <src> |

Used to get the address of a piece of a memory Load the address of <src> into <dest> |

| int | Interruptint <value> |

Used to send a signal to the kernel Call interrupt of <value>Example: int 0x80 to invoke syscall interrupt |

Structure of an Assembly Program

Before writing assembly code, understanding the core structure and how its work fundamentally is crucial. A normal assembly code typically consist of three main sections: .text, .data, and .bss

- Section

.text:- Code section is where the executable instruction resides

- The program starts execution from a defined entry point like

_start

- Section

.data:- Initialized Data section is where it stores variables that are initialized before execution

- Section

.bss:- Uninitialized Data section is used for variables that will be allocated memory but not initialized immediately

Here is a boilerplate assembly code which use NASM sytnax with x86 architecture instruction

section .data ; section declaration

msg db "Hello, World!" ; holds string

section .text ; section declaration

global _start ; default entry point for ELF linking

_start:

; write() syscall

mov eax, 4 ; put 4 into eax, since write syscall is 4

mov ebx, 1 ; put stdout into ebx, since the proper fd is 1

mov ecx, msg ; put address of the string into ecx

mov edx, 13 ; put 13 into edx because msg string has 13 bytes

int 0x80 ; call the kernel to execute syscall

; exit() syscall

mov eax, 1 ; put 1 into eax, exit syscall is 1

mov ebx, 0 ; put 0 into ebx

int 0x80 ; call the kernel to execute syscall

Refer to x86-32bit Linux Syscall Table to understand syscall number to place in EAX and the the number of arguments requirements for the rest of the registers

In the code, global _start line is use to link the code to be compile into ELF binary. It is for exporting symbols to where it will points in the object code generated. The linker will then read that symbol in the object code and its value to marks an entry point in the ELF. Here is how to compile, link and executable our helloworld.asm

$ nasm -f elf hello.asm

$ ld -m elf_i386 hello.o -o hello

$ ./a.out

Hello, World!

Syscall Calling Conventions

Based on the assembly code we just examined, how do we determine the exact values to place into registers for a given syscall? This is where calling conventions help us understand the process more deeply. Linux system calls follow a specific calling convention, distinct from standard function calling conventions in C (e.g., cdecl, stdcall, fastcall). Instead of passing arguments via the stack, Linux syscalls pass them directly through registers.

Lets take an example of syscall gettimeofday, we will explore both x86 and x86_64 in assembly and C to understand how it takes in arguments. For x86 architecture, the syscall number is placed in EAX, the first argument goes into EBX, second into ECX, third into EDX and so on. If there is more than 6 arguments are needed, a pointer to a structure containing the arguments is passed. Finally, with int 0x80 instruction is used to trigger to syscall.

Starting higher level language, which is C, here is how to implement gettimeofday syscall

#include <time.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

char buffer[40];

struct timeval time;

gettimeofday(&time,NULL);

strftime(buffer,40,"Current date/time: %m-%d-%Y/%T",localtime(&time.tv_sec));

printf("%s\n",buffer);

}

From the C code, gettimeofday function takes in two parameters. The first parameter is a pointer to the time timeval structure which represents an elapsed time:

struct timeval {

time_t tv_sec; // seconds

suseconds_t tv_usec; // microseconds

}

The second parameter of the gettimeofday function is a pointer to the timezone structure which represents timezone. Now, lets do it in assembly and take a look how the registers are used.

So, the syscall for

So, the syscall for gettimeofday is 78 in decimal or 0x4e in hex, the arguments are like before in the C code, struct timeval *tv which is a pointer to a timeval struct and struct timezone *tz another pointer to timezone struct (in the C I have set this to null).

In assembly x86, this means:

- EAX ->

78 - EBX -> pointer to

struct timeval - ECX -> pointer to

struct timezone int 0x80to invoke the syscall

However in x86_64, is slightly different:

The syscall of

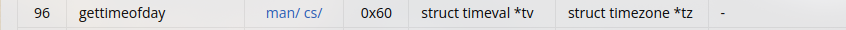

The syscall of gettimeofday in x86_64 is 96 but now it follows System V AMD64 ABI. Parameters to functions are passed in via the registers rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8 and r9.

In assembly x86_64:

- RAX ->

96 - RDI -> pointer to

struct timeval - RSI -> pointer to

struct timezone syscallto invoke syscall

Here is a short assembly implementation of gettimeofday to show how values and arguments are passed into registers

For x86 (32-bit) Assembly:

section .bss

tv resb 8 ; Reserve 8 bytes for struct timeval

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov eax, 78 ; syscall number for gettimeofday (x86)

mov ebx, tv ; pointer to struct timeval

xor ecx, ecx ; NULL for timezone

int 0x80 ; invoke syscall

mov eax, 1 ; syscall for exit

xor ebx, ebx ; exit status 0

int 0x80

and for x86_64 (64-bit assembly)

section .bss

tv resb 8 ; Reserve 8 bytes for struct timeval

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 96 ; syscall number for gettimeofday (x86_64)

mov rdi, tv ; pointer to struct timeval

xor rsi, rsi ; NULL for timezone

syscall ; invoke syscall

mov rax, 60 ; syscall for exit

xor rdi, rdi ; exit status 0

syscall

Here is the full implementation using x86 assembly: Github Gist

Stack Management

The stack is a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) data structure used for storing function parameters, return addresses and local variables. In assembly, stack is manipulate using PUSH, POP, CALL and RET instruction together with the stack pointer (ESP in x86 and RSPin x86_64)

Lets take an example where the programs take in two arguments of integers and pass it two a function to perform a sum calculation.

section .text

global _start

; Function to add two numbers

sum:

push ebp ; save old base pointer

mov ebp, esp ; set up new base pointer

mov eax, [ebp+8] ; get first parameter

add eax, [ebp+12] ; add second parameter to first parameter

mov esp, ebp ; restore stack pointer

mov ebp ; restore base pointer

ret ; return to caller

; main function that calls sum

_start:

; prepare parameters and call sum

push dword 20 ; second parameter (pushed first)

push dword 10 ; first parameter (pushed second)

call sum ; call sum function

add esp, 8 ; clean up parameters (2 params)

mov ebx, eax ; move sum result to ebx for exit

mov eax, 1 ; syscall number for exit

int 0x80 ; make syscall

Here how the code execution flow and stack management:

_startfunction prepare arguments and callssumfunction- Push

20onto the stack ->push dword 20 - Push 10 onto the stack ->

push dword 10 - Call

sum-> push return address (next instruction aftercall) onto the stack and jump tosum

- Push

Initial Stack State (growing downward):

High Address ┌──────────────┐

│ Environment │

│ Variables │

├──────────────┤

│ argv[] │

├──────────────┤

│ argc │

├──────────────┤

ESP → │ Return Addr │ (From `_start` caller)

└──────────────┘

Low Address

After pushing parameters:

After pushing parameters:

┌──────────────┐

│ Environment │

├──────────────┤

│ argv[] │

├──────────────┤

│ argc │

├──────────────┤

│ Return Addr │ <-- (From `_start` caller)

├──────────────┤

│ 10 │ First parameter [EBP + 8]

├──────────────┤

ESP → │ 20 │ Second parameter [EBP + 12]

└──────────────┘

Sumfunction executes- Save old base pointer ->

push ebp - Set up new base pointer ->

mov ebp, esp - Get first argument (10) ->

mov eax, [ebp + 8] - Get second argument (20) and add it ->

add eax, [ebp + 12](in EAX already containing first argument value) - Restore stack pointer ->

mov esp, ebp - Restore base pointer ->

pop ebp - Return to caller ->

ret(Pop return address into EIP) Insidesumfunction, it has the prologue ofpush ebpandmov ebp, espto set up a new stack frame.

- Save old base pointer ->

┌──────────────┐

│ Environment │

├──────────────┤

│ argv[] │

├──────────────┤

│ argc │

├──────────────┤

│ Return Addr │ <-- (Stored return address from _start)

├──────────────┤

│ 10 │ First parameter [EBP + 8] before call

├──────────────┤

│ 20 │ Second parameter [EBP + 12] before call

├──────────────┤

ESP → │ Return Addr │ <-- (From `_start` -> `sum`)

└──────────────┘

Here it will access the parameter by loading into eax where 10 move into EAX and then adds with 20. Now EAX is 30

After entering sum function (after push ebp):

┌──────────────┐

│ Environment │

├──────────────┤

│ argv[] │

├──────────────┤

│ argc │

├──────────────┤

│ Return Addr │ (From _start → sum)

├──────────────┤

│ 10 │ First parameter [EBP + 8]

├──────────────┤

│ 20 │ Second parameter [EBP + 12]

├──────────────┤

EBP → │ Old EBP │ (Saved EBP from `_start`)

ESP → ├──────────────┤

│ (Free) │ <-- Stack grows downward

└──────────────┘

Finally, the stack cleanup process:

mov esp, ebp-> restores stack pointerpop ebp-> restores caller’s base pointerret-> pops return address intoEIPand jumps back to_start

┌──────────────┐

│ Environment │

├──────────────┤

│ argv[] │

├──────────────┤

│ argc │

├──────────────┤

ESP → │ Return Addr │ (From `_start` caller)

└──────────────┘

We have covered the fundamentals of assembly, next will be writing shellcode and knowing some pwn exploitation technique.

- Hello World in shellcode

- Encoding techniques (NOP sleds, XOR encoding)

- Null byte avoidance